Grateful to the inimitable Richard Polt for his own post about the quixotic Ed Abbey this morning–check it out!

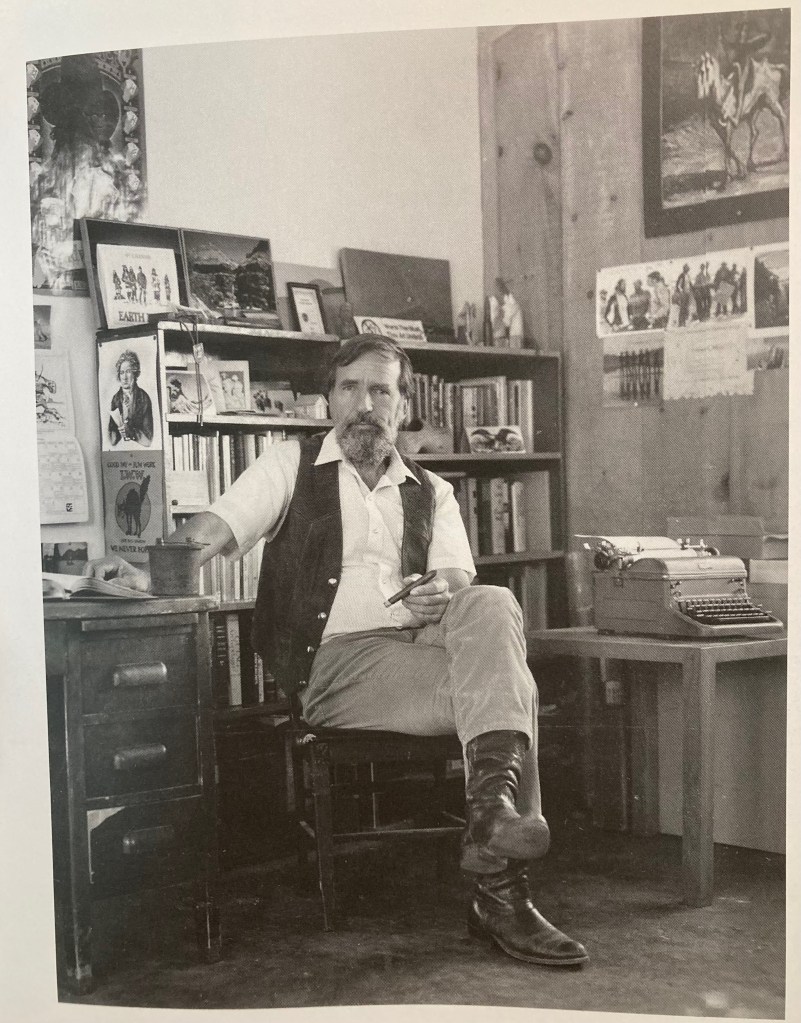

We all have relations. This is one of mine: Edward Abbey, writer, naturalist, anarchist, and hellraiser. He is my first cousin, once removed, as I finally established and wrote down for my eldest son, so I would never forget it again. Thus:

Edward Abbey’s father was Paul Revere Abbey (1901-1992). Paul Revere Abbey’s father was John Henry Abbey (1850-1931): he is the grandparent my grandma and Edward Abbey have in common.

John Henry Abbey and his wife, Eleanor Jane Ostrander (1856-1926) had eight children, and Paul Revere Abbey was the youngest. The eldest, Estella Wilhelmina Abbey Bake (1880-1960), had two children: Joseph Abbey Bake (1908-1979), and my grandmother, Estella Mae Bake Howard (1915-1989). Grandma Stell, as we knew her, married Clyde Dehn Howard (1915-1976), who was my Grandpa Clyde. Their one child was my mom and your grandma.

This is the sort of thing I find myself doing intermittently over the last five years or so, since Covid. Theorizing the blood that runs through my veins based upon available records.1 Finding firm ground for my feet beneath the shifting daily sands of an increasingly-virtual life. Who am I, really? Well, that is each of ours to answer–but demonstrably, I am of these folks.

Cousin Ed has been in my mix for decades, vaguely. I knew he was a semi-famous relation, but I didn’t know what to do with him. If you are from the Southwest, or love the desert, or are a hellraiser conservationist yourself, you probably know him. I was none of these three. I was born in Salt Lake City, but have lived in the east my whole conscious life except for–like him–a formative year at Stanford.2 He rose to prominence upon the publication of Desert Solitaire in 1968, and again with his novel The Monkey Wrench Gang in 1975. But he wrote and published incessantly beyond these two works, and was never satisfied with being a “mere” nature writer. Like so many authors, he always felt his best work was in front of him, and that he was not delivering on his potential. He was by most accounts a complicated and difficult person. Like most people I admire, I emulate some parts of him, and not others.

My university library has an astonishing number of his works in the collection. I imagine this is because two generations ago, he typified an independent and ferocious champion of the natural world against development. And a university in the southern Appalachians can really get behind that, especially one that grew to embrace “sustainability” as one of its primary brands. He wrote on my region too, a bit; born in Home, PA, he claimed an Appalachian heritage, before decamping to Utah and Arizona. But he also taught for a year at what is now Western Carolina University, two hours away in Cullowhee, and hated it (“all those pink faces in the classroom three f–ing hours, five f–ing days per week…always there’s tomorrow’s s–t to prepare. to read, to grade…”). Like I said: complicated.

I am drawn to him right now, though, because of his unfailing commitment to calling out the truth even when his world would prefer most folks to believe untruths. Because this feels like my business right now too–in a different but equally precious realm that is in the process of being pillaged and ruined.

To him, one of the undeniable truths of his time was that those officially interested in preserving and honoring the natural world were actually pursuing profit, and were convinced that growth was always a positive goal. “Growth for the sake of growth is a cancerous madness,” he declaims in Desert Solitaire: by definition, the development of American wilderness into “accessible” national parks destroys much of what makes them precious to experience in the first place.

He is tireless in asserting that once the desert is broken apart, interpreted, and rendered into bite-size chunks that can be consumed through a car window on a blacktop highway, it is already gone.

There is something about the desert that the human sensibility cannot assimilate, or has not so far been able to assimilate…even after years of intimate contact and search this quality of strangeness in the desert remains undiminished. Transparent and intangible as sunlight, yet always and everywhere present, it lures a man on and on, from the red-walled canyons to the smoke-blue ranges beyond, in a futile but fascinating quest for the great, unimaginable treasure which the desert seems to promise. Once caught by this golden lure you become a prospector for life, condemned, doomed, exalted.

This is a milder expression of his concern than you will find elsewhere in the book, and in his letters. He seems pretty uninterested in adjusting his message to suit the sensibilities of his readers and listeners. He just knows he is right, and that the world that thinks otherwise has to be called out for their destructive foolishness. He doesn’t care if his message makes you uncomfortable. He doesn’t work for you.

Human Words Project started as an expression of alarm upon the public release of ChatGPT in fall 2022. The alarms have only grown louder as universities across the county have resigned themselves to accepting the capacity to use AI as a new turnkey job skill, which of course has to be on the syllabus.

Granted: I am in a college of education, and know through participation in campus-wide efforts to craft policy and guidance for our colleagues that there are plenty of critical sites elsewhere in the academy. But witnessing the wholesale turn of teachers to AI, at all levels, leads me to mourn a rapidly-vanishing time when the skills of shaping words to achieve specific ends are themselves outcomes of school. We are certainly hurtling toward a horizon that regards wordmaking as a drudgery to be automated, whenever possible, like dishwashing, or digging post holes.

Perhaps some wordmaking is: the necessary, purely “efferent” texts, as the no-longer-fashionable reading theorist Louise Rosenblatt styled them, can perhaps be automated through pattern-recognizing digital agents. Though today we laugh hollowly at how willingly a programmed-to-please AI just makes up substitute facts about, say, recommended books for summer reading.

Is there such thing as a text only about meaning that can be “carried away”? Where would you draw the line around information to be communicated that has no “aesthetic” element? Weather reports? Sports scores?3

And Cousin Ed will have none of it! He says it is supposed to be hard to get to things worth seeing! The easy, paved road, with attendant comfort stations and Coke machines, make places of wild beauty into an entirely different, hopelessly diminished thing.

In Desert Solitaire‘s “Polemic: Industrial Tourism and the National Parks,” he lays it out plain (much quoted, but needs to be here in its entirety):

There may be some among the readers of this book, like the earnest engineer, who believe without question that any and all forms of construction and development are intrinsic goods, in the national parks as well as anywhere else, who virtually identify quantity with quality and therefore assume that the greater the quantity of traffic, the higher the value received. There are some who frankly and boldly advocate the eradication of the last remnants of wilderness and the complete subjugation of nature to the requirements of—not man—but industry. This is a courageous view, admirable in its simplicity and power, and with the weight of all modern history behind it. It is also quite insane. I cannot attempt to deal with it here.

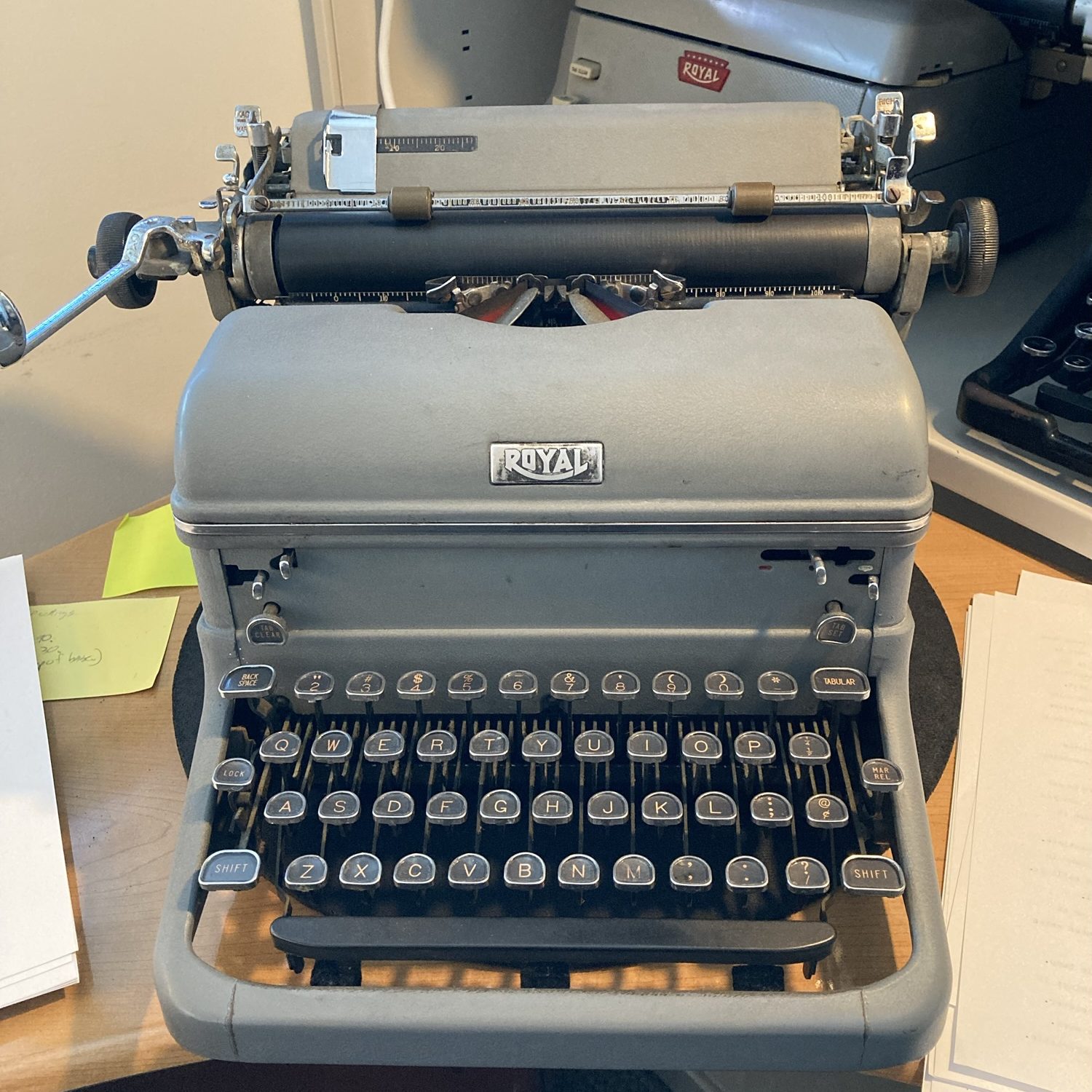

Well, I am trying to deal with it. I think Abbey would agree, were he still among us: Our human words are the some of the last wild places we can visit, enjoy, and share. And they are ALL our wild places–as close to hand as a pen and paper, a typewriter, a letter, a book, a conversation. Why in the world would we abandon them to development, in the name of convenience and efficiency, to enrich those who would sell us the lie?

Cousin Ed is exactly the companion I need for this journey down the river: someone else who will fight you to put an uncrossable line around something precious.

A river that, like his beloved Glen Canyon, seems doomed. Desert Solitaire‘s longest essay is a memoir of a ten-day float through it–a journey remembered years later, as the author is assembling the book and remarks that the Glen Canyon Dam has flooded everything he saw and remembers.

Again, his words are better:

The beavers had to go and build another goddamned dam on the Colorado. Not satisfied with the enormous silt trap and evaporation tank called Lake Mead (back of Boulder Dam) they have created another even bigger, even more destructive, in Glen Canyon. This reservoir of stagnant water will not irrigate a single square foot of land or supply water for a single village; its only justification is the generation of cash through electricity for the indirect subsidy of various real estate speculators, cottongrowers and sugarbeet magnates in Arizona, Utah and Colorado; also, of course, to keep the engineers and managers of the Reclamation Bureau off the streets and out of trouble.

The impounded waters form an artificial lake named Powell, supposedly to honor but actually to dishonor the memory, spirit and vision of Major John Wesley Powell, first American to make a systematic exploration of the Colorado River and its environs. Where he and his brave men once lined the rapids and glided through silent canyons two thousand feet deep the motorboats now smoke and whine, scumming the water with cigarette butts, beer cans and oil, dragging the water skiers on their endless rounds, clockwise.

PLAY SAFE, read the official signboards; SKI ONLY IN CLOCKWISE DIRECTION; LET’S ALL HAVE FUN TOGETHER! With regulations enforced by water cops in government uniforms. Sold. Down the river.

Once it was different there. I know, for I was one of the lucky few (there could have been thousands more) who saw Glen Canyon before it was drowned. In fact I saw only a part of it but enough to realize that here was an Eden, a portion of the earth’s original paradise. To grasp the nature of the crime that was committed imagine the Taj Mahal or Chartres Cathedral buried in mud until only the spires remain visible. With this difference: those man-made celebrations of human aspiration could conceivably be reconstructed while Glen Canyon was a living thing, irreplaceable, which can never be recovered through any human agency.

(Now, as I write these words, the very same coalition of persons and avarice which destroyed Glen Canyon is preparing a like fate for parts of the Grand Canyon.)

What follows is the record of a last voyage through a place we knew, even then, was doomed.

He has been around long enough to remember how it used to be: he keeps fresh the account of what has been lost in the rush to development, and will not be told it was worth it.

Well, neither will I. But our words aren’t gone yet. We can make the quixotic effort to push back the dam and keep the river.

I was perhaps an unsuccessful Spanish major, in that I failed to read Don Quixote, in either language. But I did gather its message that maybe the apparent fools are really the wise ones–because they can discern what is essential, and will struggle immoderately to protect it.

May we all be so foolish.

- The “available records” have also established genetically who my father’s birth parents were. That story is a post for another day, unless I already made it and am forgetting–but it’s a doozy. ↩︎

- His was a Wallace Stegner Creative Writing Fellowship 1957-58, the year before Wendell Berry did his. Apparently the two were fast friends ever after. They shared a moral commitment to honoring and preserving our natural world, but conducted themselves according to its dictates in dramatically different ways. ↩︎

- c.f. The ever-prescient David Foster Wallace, describing aspiring-sportscaster Jim Troeltsch in Infinite Jest, pp 308-309. This will be my last footnote. “The sports portion of WETA’s broadcast is mostly just reporting the outcomes and scores of whatever competitive events the E.T.A. squads have been in since the last broadcast. Troeltsch, who approaches his twice-a-week duties with all possible verve, will say he feels like the hardest thing about his intercom-broadcasts is keeping things from getting repetitive as he goes through long lists of who beat whom and by how much. His quest for synonyms for beat and got beat by is never-ending and serious and a continual source of irritation to his friends.” . ↩︎