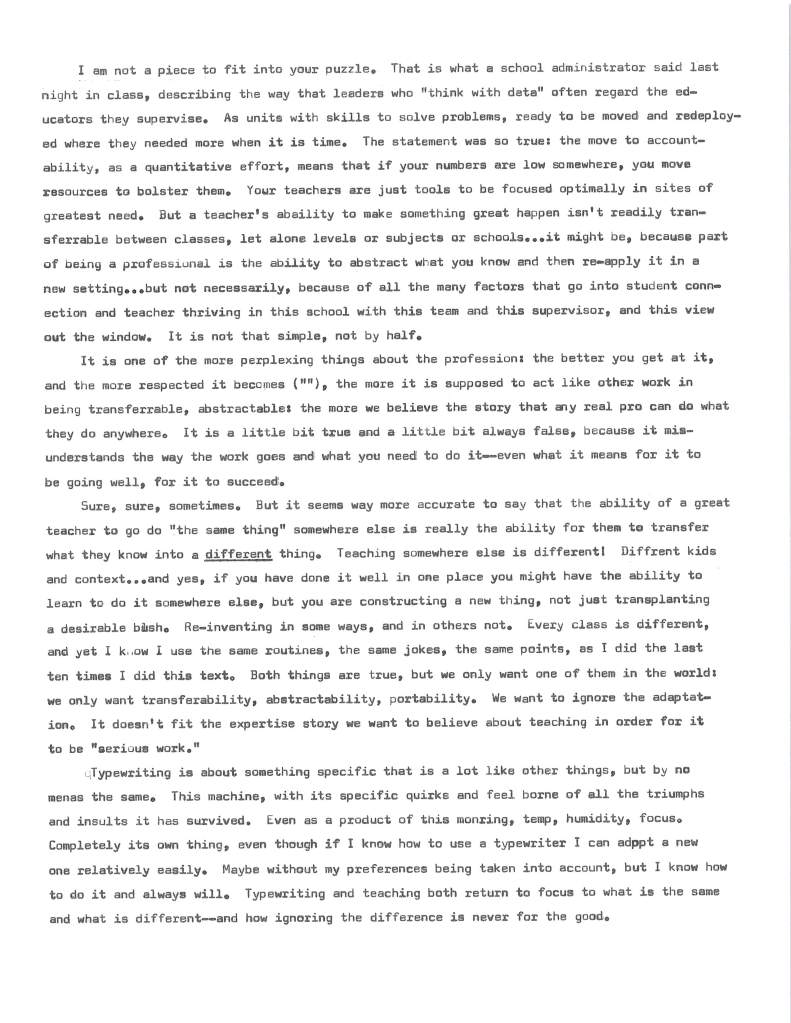

Here are a couple of pages I typed this morning on my ’67 Hermes 3000.

Well: first, here is the ’67 Hermes 3000 in question. My ten year-old named all my typewriters when he was in my office last month, but I have mixed up the placards. This is either “Smith” or “Inigo Montoya.” It will probably answer to either.

I am in love with the wonderful ease with which a typewriter like this calls you in to think something through. There is nothing else to do but decide what comes next on a typewriter like this. Nothing else to do but find out what comes next. Can you stay with it long enough to see?

(Oops–astute readers will note that I changed typewriters halfway through, from the ’63. Still Hermes though.)

URGENT QUESTION, for me:

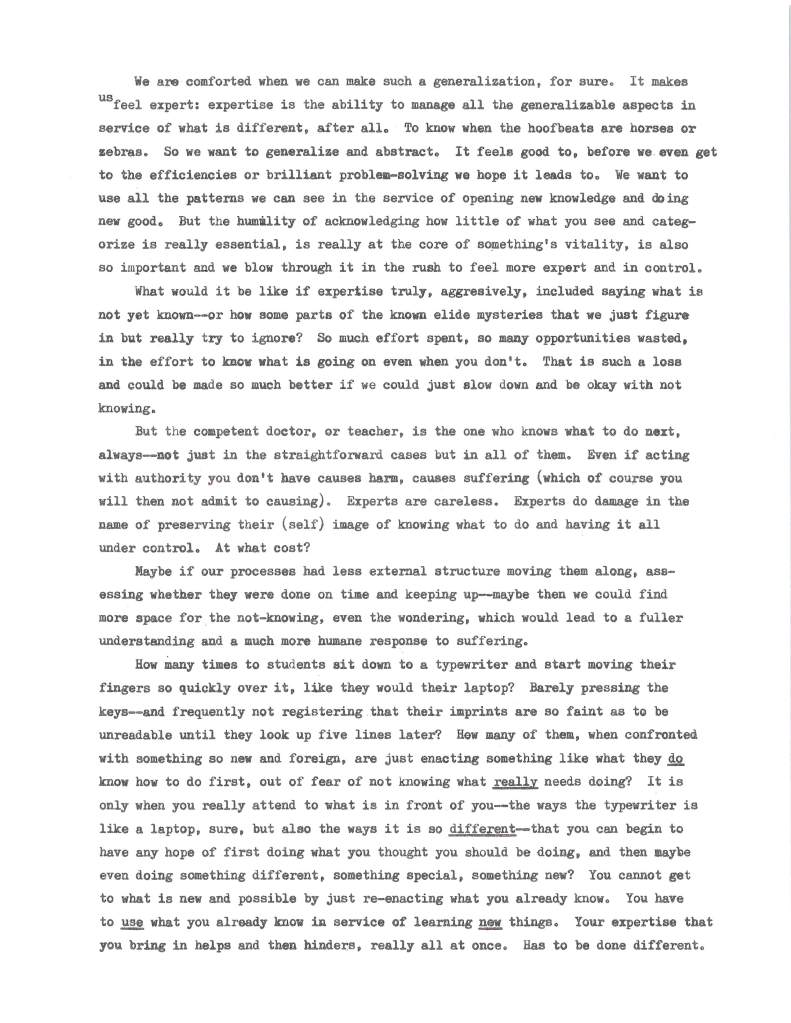

Is the first-draft typing, as above, “the writing”?

Or is it only “writing” if it gets revised, marked-up, turned into a second draft, then read and marked up again incorporating feedback? Round and round until it gets codified and published, somehow–the final version erasing memory (and if digitally edited, existence) of everything that went before?

I am convinced that our appetite for revised, polished, perfect prose is pretty much sated. Especially because machines can make perfect prose now. Boring and predictable prose, to be sure, but free of syntax error and misspellings.

Polished and perfect is easy now, and (feels) free (though isn’t).

First-draft prose, on the other hand, is now reinvented as human words, verifiably one imperfect-but-motivated human having their say to another, or many others–who might even have human words to share back.

We became allergic to typos over the decades because perfect prose was the ultimate respect for the reader. And the capacity to make that perfect prose was the ultimate sign of writing expertise. I honor you enough to conform to your expectations of how this will be put together, our careful proofreading said: I care enough to remove any obstacles that get between you and my meaning, intimation, implication.

Awesome–but now, can we respect our readers enough to show that we are actually people like them? Having false starts and repetitions, and misplaced fingers and smudgy ribbons–or sometimes catching fire for a page or two and producing a unitary thought that hangs together in its (im)perfect but alive way?

Can we respect our readers enough to share the real heat of what we think, rather than run the risk of homogenizing it through rewrites, or Grammarly, or god forbid ChatGPT? Is imperfect authenticity on the way as the new quality we want to find in what we read?

And if so…won’t it change how we read? Won’t we who benefited from excellent reading and writing educations, whose work was pored over with a red pen and corrected and corrected until we could correct ourselves–won’t we need to UNLEARN a lot of that? Since it has become a dead expertise, one that a machine can do better?

Won’t we want to read with a different calculus of quality: one that can’t be fooled by a machine? At least not yet?

Of course, I agree that there will always be a hunger for well-formed prose, made and revised and perfected by humans, using whatever human-throttled technology we prefer.

And there will always be those among us capable of making such prose, evolving along with the tools and holding onto their voices and our rapt attention despite tech’s incursions. I watched the Joan Didion documentary on Netflix, astounded to watch her move seamlessly from tiny portable typewriter in and after college (writing her first novel: “I sat on one of my apartment’s two chairs and set the Olivetti on the other and wrote myself a California river”) through big desktop typewriter to more expensive and better big desktop typewriter to hideous-but-state-of-the-art IBM Wheelwriter and finally, in her last years, to cowering before a massive Retina display like the rest of us.1 That’s a writer, babe. Oh yes.

And I, many of us, will always love that art. But I think we will evolve to love the first draft too. Awash in perfect, meaningless robot prose, we will learn to crave any sign of life–and what is more alive than a first draft? If it is typewritten, it might even be legible.

(Meta-moment: if you are still reading, did you scroll past the typewritten pages and jump down here to the more congenial-looking, fit-to-your-screen digital stuff? What would it take for us to WANT to read the stuff that doesn’t leap into our eyeballs most easily? If that is really where the life is?)

Will you love imperfect writing differently, in the next months and years? Writing that is different, and shows traces of its provenance in its imperfections?

As surely as a handworked quilt with uneven stitches is a precious heirloom, while a mass-produced comforter from Wal Mart is disposable?

What do you think?

(Title from what is apparently emphatically NOT a Lao Tzu quote, but I like it anyway. “If you want to become whole, let yourself be partial.” Beauty’s where you find it.)

- Just one footnote: Didion on how the word processor impacted her work. “Before I started working on a computer, writing a piece would be like making something up every day, taking the material and never quite knowing where you were going to go next with the material. With a computer it was less like painting and more like sculpture, where you start with a block of something and then start shaping it. . . . You get one paragraph partly right, and then you’ll go back and work on the other part. It’s a different thing.” Yes it is. ↩︎