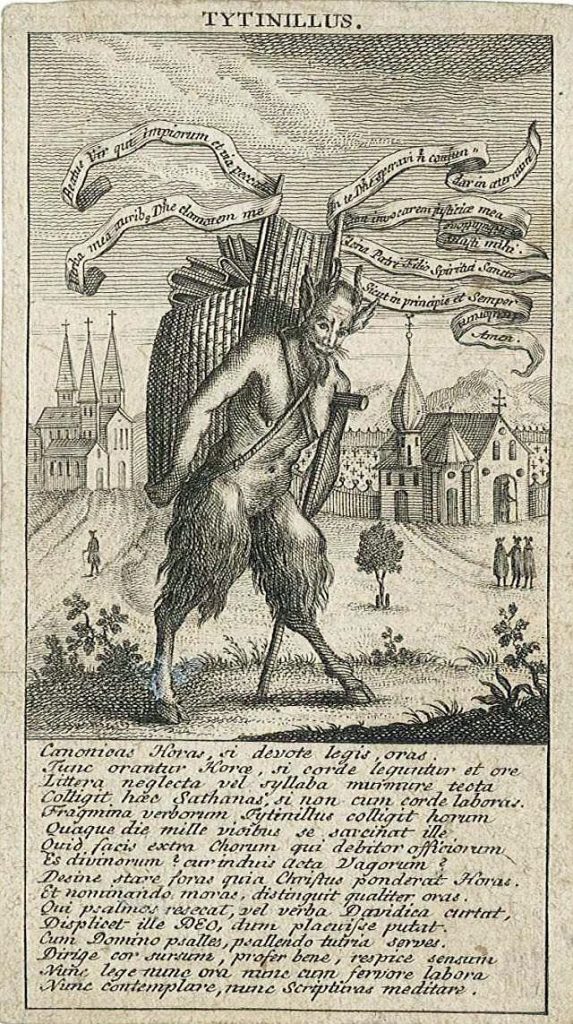

Here he is! You probably didn’t even know he existed.1 He messes up what you are trying to write. He introduced the errors that have grown like mushrooms in your draft since you last looked at it. His industry is your weakness. It’s not you–it’s him! The lord of all typos, the demon of scribes: meet Titivullus!2

I understand he was originally two demons! One who gathered up all the poorly-spoken and mumbled sermons of the preachers and prayers of the laity in a big sack–the image above has him in this form, toiling toward his quota of a thousand per day (!). And a second who compiled and tallied them, to be held against the poor mumbler and lazy parishioner on the judgment day.

Thus the medieval church installed a panoptic anxiety among the faithful.

In Margaret Jennings study of Titivillus she wrote the point of this Medieval demon was to remind clergy and laity of the danger of “spiritual sloth.” The litany of the service, each prayer and each song were to be unhurried, expressed clearly and with fervor.

To say or sing by rote and without care, to attend church, but not participate wholly was to open oneself to sin. Hence, visual reminders of a recording demon, as well as other devilish minions, were found on wood, walls and paper. In the hand-colored woodblock above three women gossip, one demon scribbles away and the second demon stretches a scroll with his teeth because they need more paper!

He sees you when you’re sleeping, he knows when you’re awake…and he knows if you have been phoning in your devotions, too. So look sharp, lest your imperfect words be held against you in the final tally and toss you into the jaws of hell (below, right).

From the demon monitoring and keeping track of our language shortcomings, it was a small step to the demon actually interpolating such errors. Mischief not just recorded, but instigated. And thus T became the active cause of our imperfections, not just their registrar.

Titivullus’s relation to Ceiling Cat’s many forms is as yet undocumented, and awaits future research.

Fun fact: he is apparently the source of the “printer’s devil,” the name given to apprenticed boys who scurried around eighteenth- and nineteenth-century printshops pulling fresh pages out of the press and collecting errant type to melt down. Because their hands were blackened by ink; because they were underfoot; because they made mischief!

Holy cow! No wonder we are so averse to typos and other false steps in our writing. We liberal arts undergrads who sort-of remember our sort-of reading of Max Weber shake our woolly (or bald) heads and think, yes: sloth in all its forms does not compute with the rational pursuit of economic gain. So mis-writing is a crime against God, and also profit.

Are we still in thrall to Titivullus? Well…does this track?

Typos are sin! And must be stamped out, even (especially?) if doing so requires an internalized self-loathing that is activated whenever we make a mistake.

Whenever we read back what we just wrote and think, that is not what I meant at all. That sounds stupid, and I misspelled “stupud” too…that voice is the spirit of Titivullus, living for free in our heads!

And loading up the very fallible (but passionate) humanity that led us to write anything at all with…well, wow, with what?

Guilt?

Nagging sense of inadequacy?

Embarrassment at having thought we had anything to say in the first place?

Much safer to not write anything at all…

And If we are already primed to feel bad about our writing’s syntax inconsistencies, then the prevalence of effortless “typesetting” technologies will make us feel even worse.

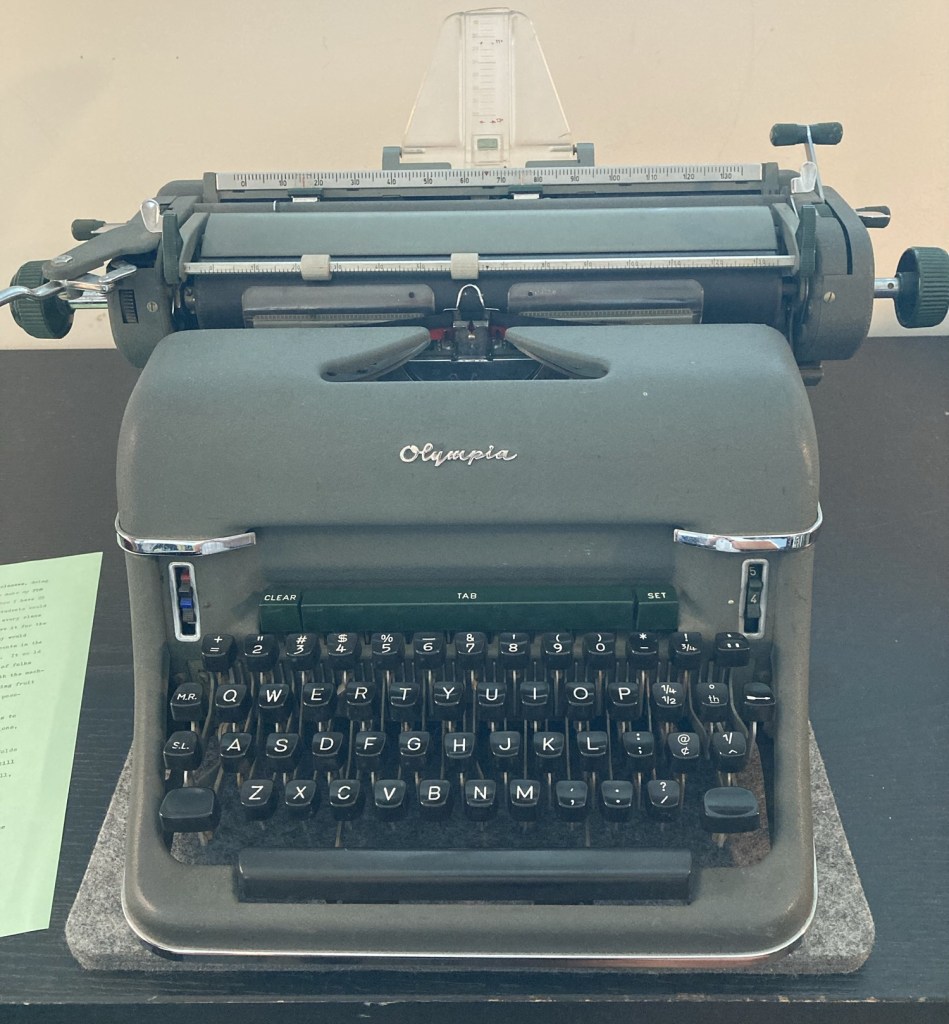

We all know two spaces after a period in word processing is a tell that your author is a recalcitrant from the age of typewriters. Word processing automates the monospace of typewriting: just put in one space and let the rock that thinks figure it out.

And everything written should look perfect now, whether or not it is actually flawless. Canva is the tip of the spear, here; a friction-free tool that raises all our expectations that whatever we dare to inscribe should be Instagram-ready, should look cute on a Stanley cup or an Etsy t-shirt.

When you know about Titivullus, you see his minions everywhere. Making you feel bad about all the ways real human words are imperfect when they first come out of us.

And making you think that until they are perfect, they are wrong and unworthy. And maybe even evil: maybe even will be held against us in some final accounting that awaits us, and our wordmaking.

What bunk, friends!

Let’s embrace an enlightened perspective that we all make and consume our words exactly the best way we can and should, exactly as we are!

Especially when the demon’s AI great-great-great grandchildren are offering us the false promise that we need never feel bad about our words again–as long as we just let them write for us. (“It’s cheating, but I don’t think it’s, like, cheating.”)

Subtle temptor indeed.

Long live typos–because they affirm the real-world and real-person provenance of what you are reading!

Go to hell, Titivullus! Let us type in peace!

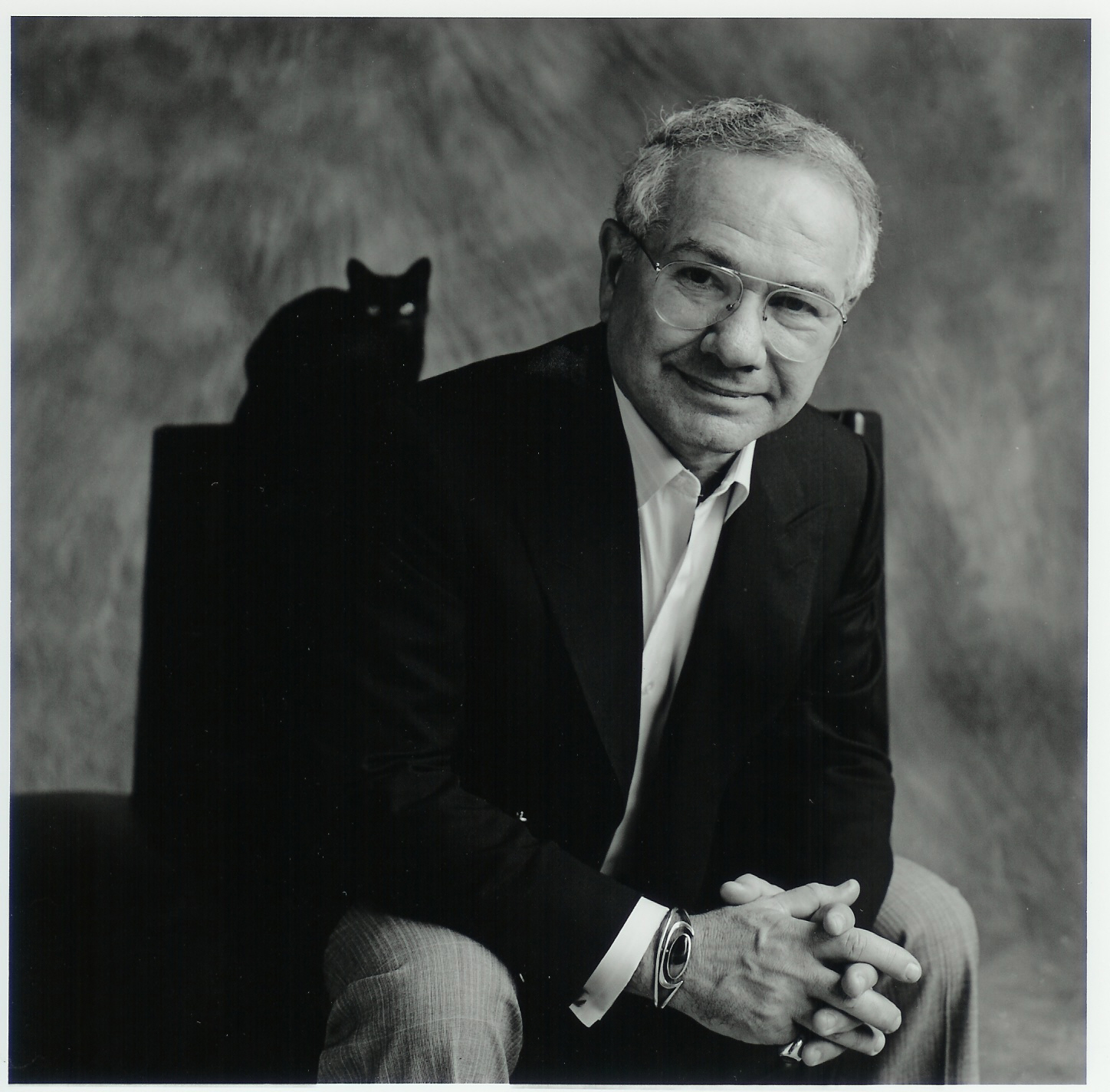

I learned tonight (Jan. 10, 2014) the sad news that Elliot Eisner has passed away. Elliot was my masters advisor at Stanford, and I owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his wisdom, his support, and his care.

I learned tonight (Jan. 10, 2014) the sad news that Elliot Eisner has passed away. Elliot was my masters advisor at Stanford, and I owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his wisdom, his support, and his care.

I remember talking to him on the phone from my little office in the Carriage House at The Field School in 1998. I wanted to go to grad school to understand why my students were having transformative experiences in my theater classes. US News and World Report said Stanford was a great place to do that, and their web site said he was the guy to talk to about it, so I called him after school one afternoon. He answered, and we talked about it for a few minutes.

In hindsight, I imagine that conversation was what got me in. If I had known his stature in the field – been smart enough to be intimidated – I never would have called. But I didn’t, and he picked up, and I guess my ignorance passed for gumption and self-confidence. Lives have been changed by dumber lucky breaks.

He was a wonderful professor, a fabulous teacher. He had a way of slowing down the room to track the deliberate speed with which he was working something out. He would speak slowly, usually in full paragraphs, his hands silently rising to gesture gracefully in the air as he made his points. I could listen to him all day, and did. He defied my best wisdom up until then about great teaching: that it was about being the loudest and most interesting thing in the room. He was quiet, barely moving sometimes, but his erudition and the architecture of his thought did the work.

He also showed me the power of thinking hard about something for a long time. If it was the right thing, you could ride it all the way to the beach, over and over. For him, the question was, “what do the arts have to teach us about education”- and he rode that wave as far as it would go, in every area, for forty years. Curriculum, assessment, evaluation, design, pedagogy, artistic experience itself: each path leading to its own more-or-less discrete book, transforming and, in some areas, re-inventing each field he explored. I read him so closely that I don’t even recognize how deeply his thought has sunk into me sometimes – I know it so well that I don’t think to footnote it. For me, its explanatory power has become common sense.

He taught me the lovely, goofy word “adumbrate,” and was so fond of it he couldn’t write five pages without using it. I drop it somewhere in most of my papers now, my little private tribute.

He dug my ideas. In my experience, we find our legs as thinkers in part because of the support offered early on by those who care about us, and he cared about me. I remember the surge I felt when he discussed my project on the use of scat language in jazz to connote what couldn’t be denoted, because it represented a relation in sound, not words. What a thrill when he got what I was driving toward, and celebrated its insights. What an affirmation.

I read Dewey’s Art as Experience in his gorgeous NoCal-funky living room, every corner crammed with statues and paintings from around the world. We ate little snacks Ellie prepared for us and tried to parse that crazy, dense book. I’ve never thought harder.

He asked my help once hauling a few huge computer monitors from his campus office to his home, back when they were like slabs of beef to lift. He drove a burgundy (I think) Porsche 911 with a vanity plate that read, “PORSCHT” (ha ha, oy gevalt). Cruising around Palo Alto in Elliot’s zip car, top down, a heavy monitor putting my legs to sleep: that’s a grand Stanford memory.

He invited me to stay and do the doctorate with him, and I turned him down, clumsily. We were expecting our first son, and I was scared about being so far from our families on the other coast. I remember a passionate talk with the head of the teacher ed program about whether or not to leave Stanford. “A degree from Stanford carries a certain…cache,” she warned. Unimaginable, to pass on such an opportunity. (“He’s already got a degree from Stanford,” murmured a smartass friend, in my defense.)

And I left badly, deciding too late for another guy to take my place – silly and immature. Still a regret of mine, but one I worked out, both with the other guy at AERA a few years later, and with Elliot when my job in Chapel Hill took me back out there for a week in 2005. He was already sick, then, but gracious: happy to have me back in his home, talk about what we did and what I was doing. Unfailingly interested, and always supportive.

In hindsight, I am very glad I left when I did. I moved on to other terrific mentors, and a life far from Palo Alto. Leaving Stanford was an early step in my ongoing effort to grow in my own self-confidence and self-worth beyond the meritocratic rat race that the academic life can cultivate in us. We can be driven by who we know, who we publish with – all the shibboleths and status signifiers that make an academic conference like the Oscars, sometimes, showbiz kids making movies of themselves. I was quite susceptible to that grift, and was well-served to get clear of much of it. There are firmer grounds upon which to build a life, for me.

But none of what I have been able to do would have been possible were it not for Elliot’s first interest in – and care of – me. I honor tonight his willingness to attend to a student, really attend; to take a call from a stranger, and to support someone’s best efforts to grow and change, to be someone else, however tentative.

There will be better tributes to the man, but this one is mine. As my semester starts, I recommit to emulating that energy and interest in my work with the students I am honored to work with now, today, tomorrow. Thank you, Elliot, for everything.

Image from Stanford’s web site.

Written and not sent; that’s what a blog is for, right? Still deeply felt. Event is tonight: App folks who read this, I’ll see you there!

– c

I was raised in a conservative religious household, and recall the concern I inherited – absorbed through my skin, like oxygen – about the depravity of some art, literature, movies, and music. I remember how I felt in my deepest heart when reading something that seemed offensive to my values, a wounding that felt like I had betrayed my God and my people by even casting my eyes, let alone my mind, on such stuff. I remember that arguments for the literary, artistic, cultural value of a such a document were unconvincing to me. If anything, they affirmed that I was “in the world, but not of it;” that, as Matthew taught me, “ye cannot serve God and Mammon,” and any rationale that Mammon offered only deepened my resistance and my greater turning toward God.

I remember these powerful experiences of wounding and healing, acceptance and rejection, as I witness our community’s controversy about the teaching of Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits to tenth graders at Watauga High. Arguments against the book have turned on the unsuitability of its sexually explicit and violent passages for inclusion in curriculum. Defenses have included appeals to the work’s universally-recognized literary merit (even, in a letter to the county school board, by the author herself), character references of the teacher involved, and insistence that the book is approved for inclusion in the tenth grade curriculum and that an alternate was offered (so, really, why should anyone be upset)?

I am torn up about how this dialogue is unfolding: how closely it follows the narrative of so many controversies about curriculum. It seems initially to be about legality and literary quality, each side trying to educate the other about risks and benefits it apparently cannot conceive. But I am beginning to see that the core issue is actually the authority we give or withhold from the school to speak into deeply-held differences of our society. The Reagan-era school prayer flap was the first time I noticed the conflict. In our times it includes evolution/creationist science curricula, sex ed, political advocacy, The Pledge of Allegiance, Scouts in the cafeteria in the afternoon, and on and on. We are a deeply divided nation on many fronts, and the school is the brightest flashpoint as we work out our own anxieties through the presumably more manageable lives of our children. We don’t know what we want our schools to do for them (us), how uncomfortable we are willing to let school make them (us). So we fume and fret and grumble to those who agree with us about what the world is coming to as the other side drives us into the ditch.

My best response to this tension comes out of what happened to me after I left home. I attended a university with an unfailing commitment to supporting exploration of every controversy, and trusting that that the community, through respectful dialogue, would find its way. I encountered attitudes and values at school that were deeply different than mine, and as a result found my own changing: about culture, politics, gender, sexuality, and ultimately the nature of my faith. Through respectful – though sometimes heated – discussion and argument, and open-hearted listening to those who were not me (i.e., everyone), I came to understand just how different others were than me. And that my own values, however deeply held, simply could not serve as an index of what someone else knew and felt about the world.

This is perhaps the greatest possibility offered by public school, greater than basic skills training, job readiness, even Friday night football: the possibility to allow all who make up this community to see deeply into each other’s otherness – perhaps to realize, at core, that we are exactly the same in our passionate need to have our otherness understood and respected.

That’s why I support the teaching of The House of the Spirits, unequivocally, and the teacher who chooses to teach it. The book is an opportunity to have that kind of discussion, that kind of listening and understanding of each other. But I refuse to support teaching the book by making those who oppose it into cartoons of intransigence and closed-mindedness. (After all, it’s only a matter of time before this controversy makes national news, and the rest of the country remains completely willing to retell that story about who we are in the High Country. Can’t we be better to each other?) I believe that school is where our students should – must – respectfully encounter, engage with, and come to understand points of view that differ profoundly from their own. And our larger community must be a place where we can do the same with each other. If I presume to have the only clear vision of what is valuable, I am as blind as my worst caricature of those who disagree with me.

I plan to attend the community-wide read-in and teach-in of The House of the Spirits ( 7:00 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. Dec. 3 in Belk Library, Room 114, on ASU’s campus), and I hope you will too. I would be happy to organize another one in the common room of our excellent Public Library. I hope these events will be a chance for all of us to share the book and make our own judgment; share our own experience of reading and encounter of ourselves and each other. May we all go back to school, as we focus the energy this controversy has ignited. Focus it toward hearing, seeing, reading each other fully, perhaps for the first time.