I might get to yell “first” in the Typosphere for blogging this terrific NYT article on the rediscovery of the “MingKwai” Chinese typewriter.

It details the thrill of Tom Mullaney, an obsessive history professor (I thought I had it bad) searching out, finding, and saving the only extant example of this machine from oblivion.

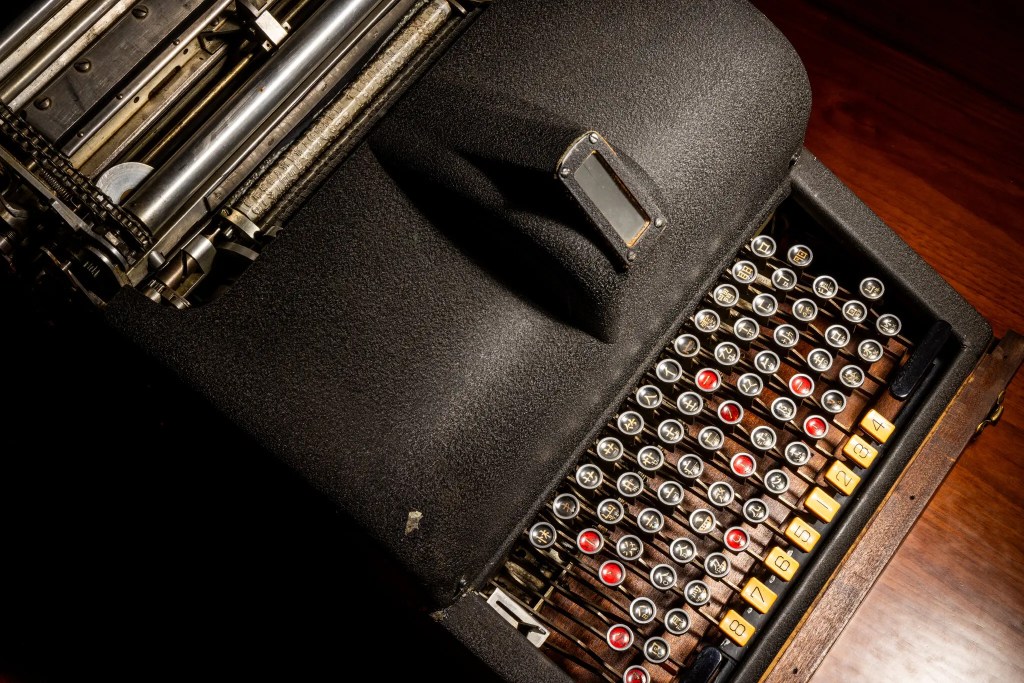

I have never seen any Asian language typewriter in person, but the gorgeous photos here really give a sense of the engineering feat accomplished in this protoype.

Imagine!

Any two keystrokes, representing pieces of characters, moved gears within the machine. In a central window, which Mr. Lin (YuTang, the inventor) called the Magic Eye, up to eight different characters containing those pieces then appeared, and the typist could select the right one.

Mr. Lin had made it possible to type tens of thousands of characters using 72 keys. It was almost as if, Dr. Mullaney said, Mr. Lin had invented a keyboard with a single key capable of typing the entire Roman alphabet.

He named his machine MingKwai, which roughly translates to “clear and fast.”

It was never manufactured. Lin had a single prototype made in the 30s at his own enormous expense, and tried to sell it to Remington, the General Motors of the era’s American typewriter industry. It failed during the demo; he went bankrupt; the machine was stashed at his job, then moved here, then there, and was presumed lost.

“Gone the way of most obsolete technology…had most likely ended up on a scrapheap. The right person hadn’t been there to save it, to tell its story.”

What is worth saving?

I think typewriters tend to be! My typewriter collection does not enter Dr Mullaney’s rare air, for sure. All of my machines were made in the hundreds of thousands, if not more, and none could be considered truly scarce. Though some, like the 1967 Hermes Ambassador that tops my blog, are definitely scarcer than others.

But the course of the Ambassador is exemplary of the path I think once-precious things often take when they become outmoded. It got stashed in the back of a dry closet, under a cheap plastic cover someone had the presence of mind to replace before forgetting about it for decades. And that afterthought by some anonymous someone is why it surfaced in an estate sale, perfectly functional, when so many others that were left uncovered in damp basements or attics do not. (Cover your typewriters, children!)

I think so many manual typewriters are still around because they were so expensive. They were workaday tools–well, some were more stylish than others, and they had different price points, so maybe they were more like automobiles than tools–but they were dear to acquire, about the price of a laptop today. So even when they were no longer needed, and were replaced by an electric or a desktop computer, folks couldn’t imagine tossing them out.

That cover wasn’t an afterthought. The Ambassador was a luxury model! I like to imagine that it was the owner’s child, or grandchild, that finally made the choice to store it safely. Maybe because they had been told over and over that it wasn’t a toy. You can’t play with it. It’s precious. Treat it like something precious. And that someone–or their child–did.

So maybe that’s why one generation’s expensive stuff tends to still be around for future generations to rediscover, reassess, and decide if it has anything new to offer in a present-day recontextualization. The kids get told to take care of it–and they do.

But…what about the true ephemera of our daily lives? Will we miss any of it when it is gone?

Cruise FB Marketplace’s “free stuff” section in a college town right around the end of July, when all the student apartments are turning over, and wonder. Will anyone ever miss flatpack furniture? Entry-level vacuum cleaners? Futons? (So many futons.)

So much hideousness. Here in my personal college town, our sustainability-branded university students used to collect all the discarded stuff, spend a few weeks cleaning and sorting it, and then sell it back to the incoming frosh in “The Big Sale” that happened at Legends, proceeds to scholarships. A one-day Black Friday delirious feeding frenzy of plastic and upholstery and area rugs. It was a gas.

Unimaginable with social distancing, “The Big Sale” got cancelled during COVID…then, like so many things, just quietly never started up again.1 I have a mediocre electric fan from the last one in 2019. It cools nothing, but reminds me of stomping around the bedlam of that sunny hot morning in a packed Legends with my then six-year-old in wide-eyed tow. Glorious memory.

You miss the ephemeral stuff if you have reason to miss it; you miss stuff if it has a reason to matter. It was from the last “Sale.” I didn’t know it was the last sale, any more than Lin knew the typewriter would be the only one ever made. The meaning got loaded into it after.

And of course you can’t save everything just in case it matters later–because that is the high road to hoarding. If you never throw anything out, how will anything ever be precious?

You have to miss something for anything to matter. Like Sheryl Crow sang, “there ain’t nothin’ like regret / to remind you you’re alive.” Better to lose too much and make space for the new, run the risk of having tossed something you long for, than be hemmed in by stacks of everything in case some of it happens to matter to you again…

Right?

So: save some of it, I guess?

Maybe that is how to honor a past you were part of–and, eventually, as you grow older and more judicious about what is beautiful, a past you weren’t part of too.

But also, let the world have its way with ephemera, which of course is most everything. Burn through stuff made to be burned through.

What matters will become clear later…and we will have the delectable chance then to rediscover what once we could not even see, and treasure it up in our new world for the preciousness it brings us from the old.

- Besides, Legends was torn down this week. Victim of Helene, supposedly–but also was hard to program the last few years, and nothing that doesn’t fill up right with value stays as-is on this campus. Will it be missed? Maybe if you saw Hank Williams Jr there, or Dave Matthews, or A Tribe Called Quest…some hyperlocal cred to be collected if you did. I saw a great band there once featuring students I taught in middle school twenty years earlier. That is enough for me to miss it–especially because it will almost certainly be replaced with some “nice”, institutional building with all the soul of a Holiday Inn Express. ↩︎