On this Halloween morning, I awake gnawing on an unexpected seasonal treat: a new-to-me horror film that delivers on all the creepy potential that makes me love the genre above all others.

And there’s a typewriter in it too! Which, like most typewriters for most of their existence, doesn’t seem to matter that much—but actually might be the most potent symbol in this story of power craved and feared, hidden and revealed.

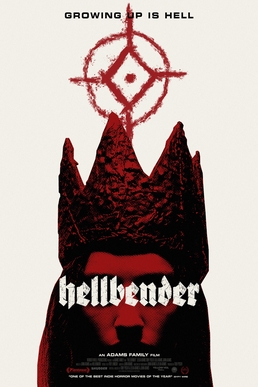

The film is 2021’s Hellbender, by the independent film-making Adams Family. Married and creative partners John Adams and Toby Poser created it with their adult daughters Zelda and Lulu Adams, on their Catskills property during the Covid lockdown. And it is shot through with family intimacy and trust and dread (as well as some deliriously batshit dream sequences).

The performances come right off the screen at you in the familiar ways real-life mother and daughter connect, resist, negotiate, and eventually evolve their relationship the only way it can go. Not since Let the Right One In have I seen domestic and supernatural powers woven together so deftly and effectively.

Its provenance is almost otherworldly: can any family be this cool? But the resulting film gets its oomph from the reality of its surroundings. A restored nineteenth-century house with Shaker-white walls and spare furnishings hiding dark recesses; a bougey outdoor pool where ancient and modern forces sniff each other out and negotiate inevitable collisions; the revolving seasons of the gorgeous and terrifying woods, fields, streams, and creatures of rural New York state, an uncredited but witnessing presence.

Chekhov famously said that no element in a story can be introduced without eventually becoming relevant. If a gun is shown hanging above a fireplace in the first act, goes the example, it must be fired in the third. I am no literary scholar, but Wikipedia tells me this law is meant to be broken. No less author than Hemingway loved to introduce story elements that never “go off”–because the reader’s awareness that it could go off heightens their sensitivity to what might happen, and what things might mean.

I spotted two typewriters in Hellbender, and—spoiler, sorry—neither one ever types a word.*

We glimpse one on a dresser in a bedroom, apparently a merely decorative or sentimental object (no one could really do any typing at a dresser). But the second lives atop a desk in a dark and hidden room behind the eaves, which can only be accessed through the coolest demonic user-authentication tech I have ever seen. It sits alongside an unassuming leather-bound book, among several old portraits of women ancestors who shared the mother/daughter bond the movie explores. Book, pictures, typewriter: that’s all the nerve center of an ancient sisterhood apparently needs to sustain itself.

It looks like a Smith Bros. standard from the 1910s, from what I can make of its space bar design, but I am not sure. In any case, we do not get much of a look at it. It is definitely black.

It’s the book that gets the most play, not the typewriter. The book seems to be the repository of the ancient power these women own, celebrate, struggle with. When one of them places her hand on it, she is transported through violent visions to historical moments in their lineage, as well as possible or foretold futures. There is enormous power in the words the book, we assume, holds—because books have words in them, right?

But as far as I can recall, after viewing the film only once (so far): we never see any words in the book. We never see anything in the book. The book never opens.

Toby Poser’s unnamed mother possesses immense wisdom and lore about the nature of their shared power. The combinations of herbs and roots and bark that summon various capacities, the nature of the gift / curse they bear—but I never remember her reading about these things. She just does them, and explains and demonstrates them for her daughter. The wisdom is witnessed and told, not written and read. Probably for aeons.

So…why a typewriter?

Who has written with it, and what was written?

Was what was written in the book?

Is there something yet to be written?

There is so much power swirling in the world of its film: is any of it in written words? And if not–or not yet—why is there a word-making technology at its center?

I wonder if there might be a clue in how the daughter, Izzy, explains herself to a new friend. Her first and only friend, it seems. Mother has kept daughter isolated from the world to protect the world from this power, or maybe to exert, futilely, the parental desire to save their child from pain by shaping them in their own image. (Shades of Carrie, of Firestarter…)

“What do you do for fun?” the friend asks her.

“I hike…I draw…oh, and I swim, I swim a lot.”

This answer doesn’t spark much enthusiasm from the new friend (played by Lulu Adams, Zelda’s real-life sister). So she reaches for the one other detail of her homeschooled feral-demon-child life that she hopes will give her some cred.

“I’m in a band too!”

“What do you play?”

“I play the drums…

“And I sing…

“And uh…I write the lyrics.”

This does the trick. The new friend accurately acknowledges that being in a band is cool. (Writing lyrics is cool, at least. “I dated a drummer once. He was dumb.”) And their relationship, for better or worse, begins.

The band is another mother-daughter collaboration: dark metal. We see and hear them several times in the film, mother on bass and Izzy on drums, performing in their house for only themselves. Each time they are dressed and made up differently in Ziggy-Stardust-meets-Kiss makeup and accessories. Indeed it is a band! One of the ways they connect with each other, before and while they begin to connect around the emerging understanding of the powers they share.

Mother sings, mostly—but the words are Izzy’s. Only Izzy writes in this world.

Izzy writes the lyrics.

Is the typewriter to be Izzy’s?

What else is Izzy about to write?

The movie’s logic finally becomes clear: Mother explains that their lineage reproduces by each generation consuming the one before, “like spring eats winter, and summer eats spring.” They are the titular “hellbenders”: “a cross between a witch, a demon, and an apex predator.” And in the mother’s telling, they are evolving and changing–though it is left open whether that evolution is actual, or is merely the mother’s vain hope for a kinder, gentler future for them. (Reminds of another terrific maybe-evolution, in 2016’s The Girl With All the Gifts.)

And in the midst of that ambiguity—in that promise that, one way or another, something else is about to unfold—the typewriter sits like it always has, before now. Maybe the new something will be written and shared. Maybe it will be a new book of new power. Maybe it will activate a network of holders of this ancient power that find each other through correspondence and connection. Maybe it will write the record of what has been and what might come.

We don’t know yet—but a typewriter will eventually type, even if it hasn’t yet. Its owner will find it and do with it the only thing it can do.

How terrifying, how thrilling.

How horrific!

Happy Halloween!

*I was hoping for a Fringe-type dimension-piercing magic typewriter. Maybe next time!