Ah, les plaisirs du les machines à écrire!

That is probably the only French I will attempt here—though it is hard to resist, mais oui.

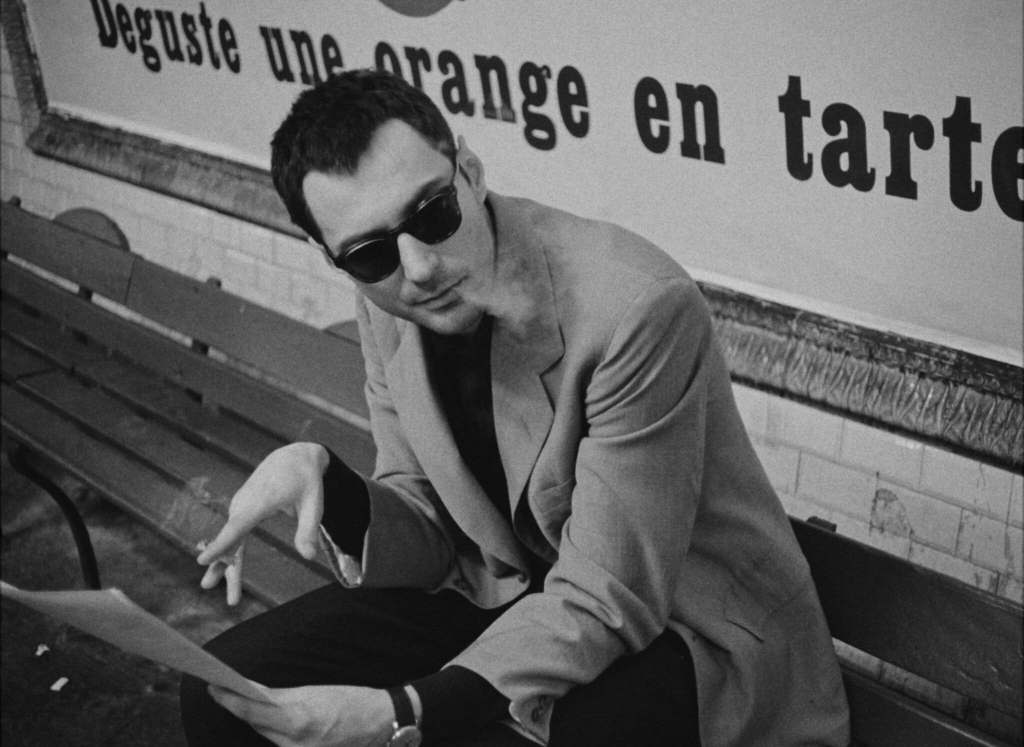

Because for the last two nights I have been submerged in Richard Linklater’s new film Nouvelle Vague, which tells a story about the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 French New Wave classic Breathless. I want to think about their typewriters, and the texts they purportedly yield.

I have watched / rewatched them both, Kanopy open in one tab and Netflix in the other. Fighting Richard Brody’s urge to make of the latter film “a nitpicker’s delight…any viewer who knows anything about Godard’s story can find contrivances, departures from the historical record. I won’t bother; if I want the details, I’ll read a book” (perhaps his).

I won’t say I really know anything about the “historical record” of Breathless. I shotgunned it only once a couple of years ago–in the name of cultural literacy, really, when my son came home from college raving about it. He was gobsmacked by his distinguished professor’s thoughts on Bicycle Thieves, and The 400 Blows, and this film, so I tried to catch up. A film autodidact at best, I do know what I like. And I liked these pictures.

In the 1959 milieu of Nouvelle Vague, typewriters are ubiquitous and unremarked. After all, Godard and his partners are the critics of Cahiers du Cinéma before they become filmmakers, so there is (supposedly) a lot of writing happening.

The offices of that magazine are imagined here as a large dining table with three high-end standard machines atop it on three sides. Two are easily identifiable as Olympia SG-1s, apparently brand new and perhaps purchased together for office use. The studio standard machine for people who write for a living, they are completely plausible presences here. First manufactured in 1953, they dominated the European and American markets. Mine is from 1960 and hulks on the table behind me right now.

The third is harder for me to make; it looks plastic and sloping, not exactly the Olivetti 82 but pretty close. We barely see it in the establishing shot of Godard, François Truffaut, and Jacques Rivette typing, and in a later shot of a brief speech by Roberto Rossellini to his assembled acolytes it is missing altogether. Perhaps it belonged to Rivette and he took it home? Pretty big machine–not for commuting! But it would make sense: another serious machine for forging a new age of film.

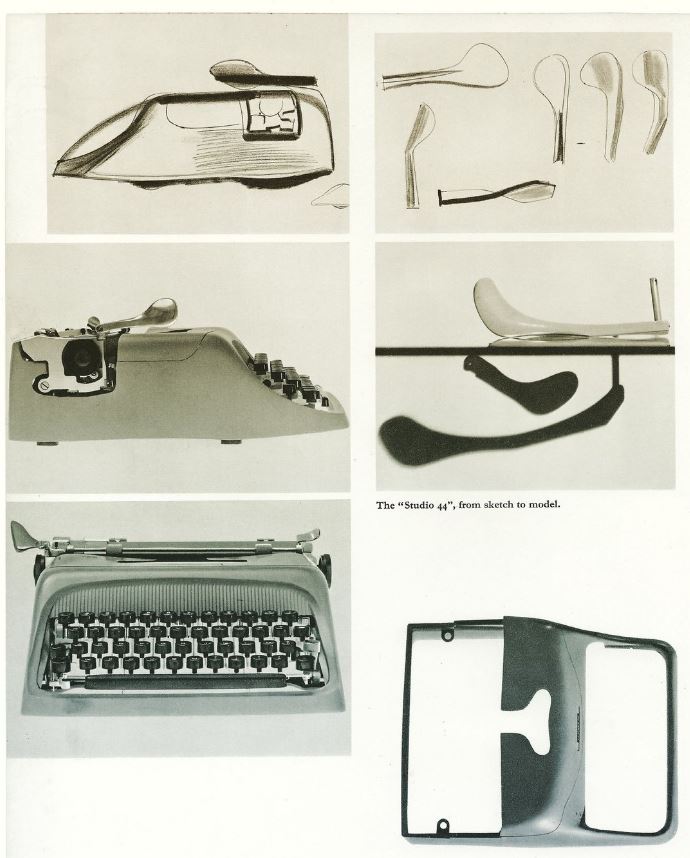

There’s also a lovely Olivetti Studio 44 in the presumed offices of the Breathless shoot itself, tucked into a corner behind Godard’s desk. I have one too, from 1961–though it began production in 1952.

He never touches it, or even acknowledges it is there; the light looks bad for serious typing on it, to me. The machine was style-forward in every conceivable way. Entirely reasonable that it would be the choice of one as presentation-conscious as Godard, so eager to make his mark in the vanguard.

Whether he ever types anything on it is unclear–and improbable, as we shall see.

But the third typewriter scene is the most interesting to me. In Breathless‘s extended afternoon almost-tryst that Patricia and Michel enjoy in the tiniest hotel room in Paris, we glimpse a portable typewriter on a cluttered desk by the bed. It is Patricia’s, because this is her hotel room. We know she is aspires to be a journalist, despite mostly just selling the Herald-Tribune rather than writing for it, and she also notes that she will have to enroll at the Sorbonne in order to keep her financial support flowing from home in the United States. (From where in the US is unclear to me–though Jean Seberg was born in Iowa, as her flatly-accented French reveals whenever she opens her mouth.) These are all good reasons to have a neglected typewriter on your premises.

And the typewriter is the least interesting thing on that desk in the original film. There is paper in it, but it mostly serves as a flat surface for a hat to rest upon. Later it supports a radio that plays “music to work to”–and is promptly switched off, since its strident tones interrupt the afternoon-delight reverie each is enjoying on different terms.

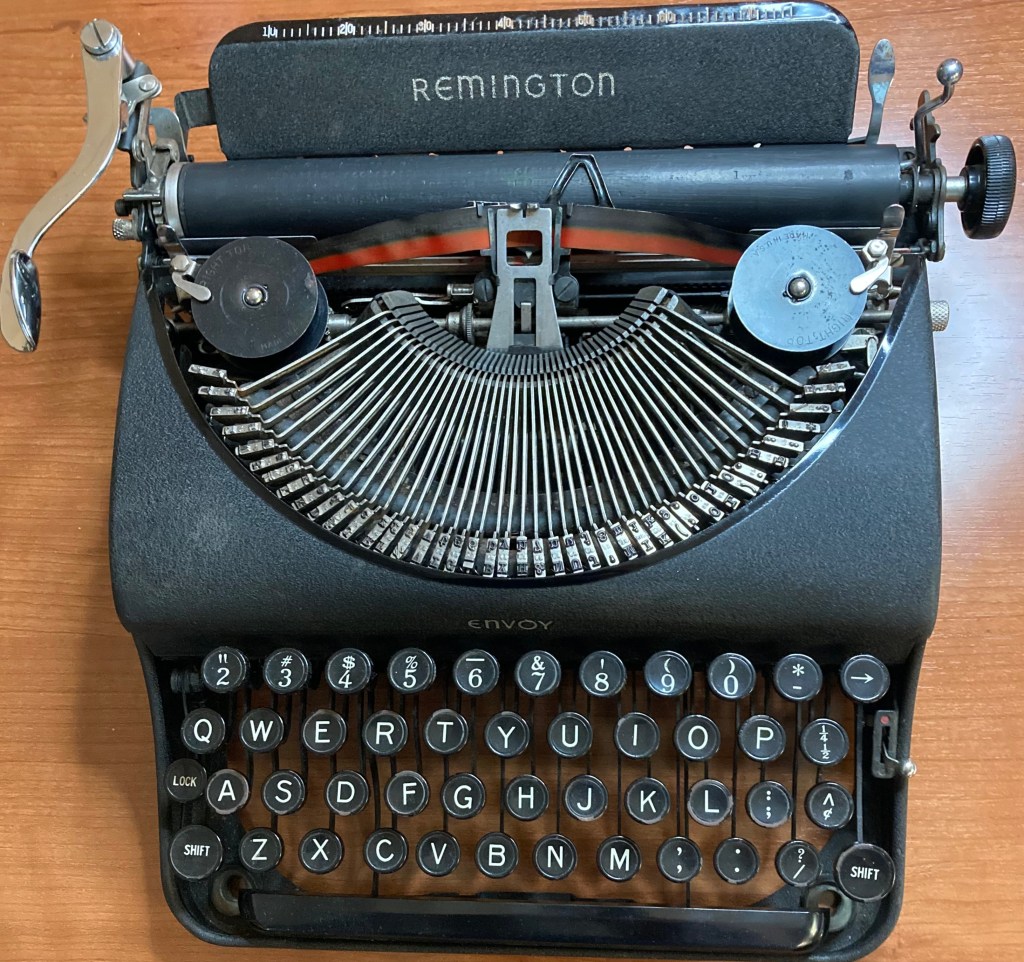

I would guess it is a Remington, by its round keys and distinctively-hooked carriage return lever. It could be an Envoy Type 2 like the beautiful one I own. Manufactured in 1941-42, and indestructible as a cockroach, it is a sensible machine for a budget-conscious gamine to be carting to Paris seventeen years later. So far so good.

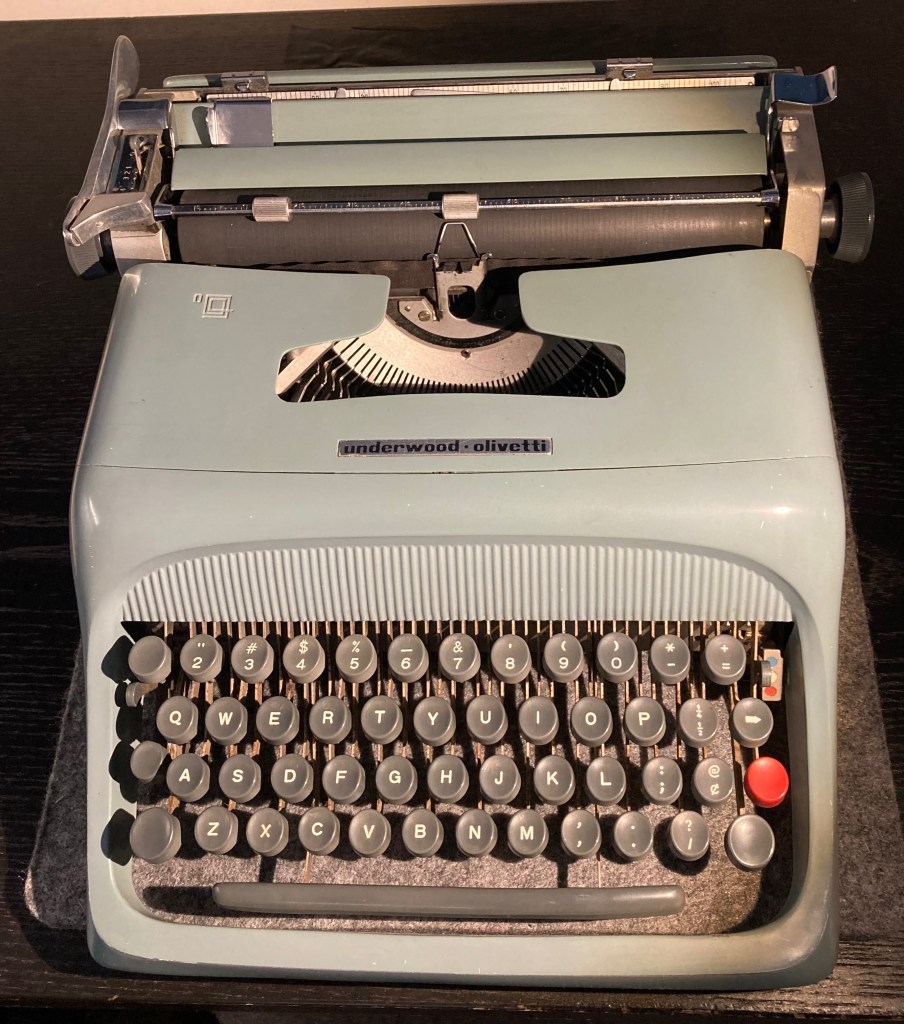

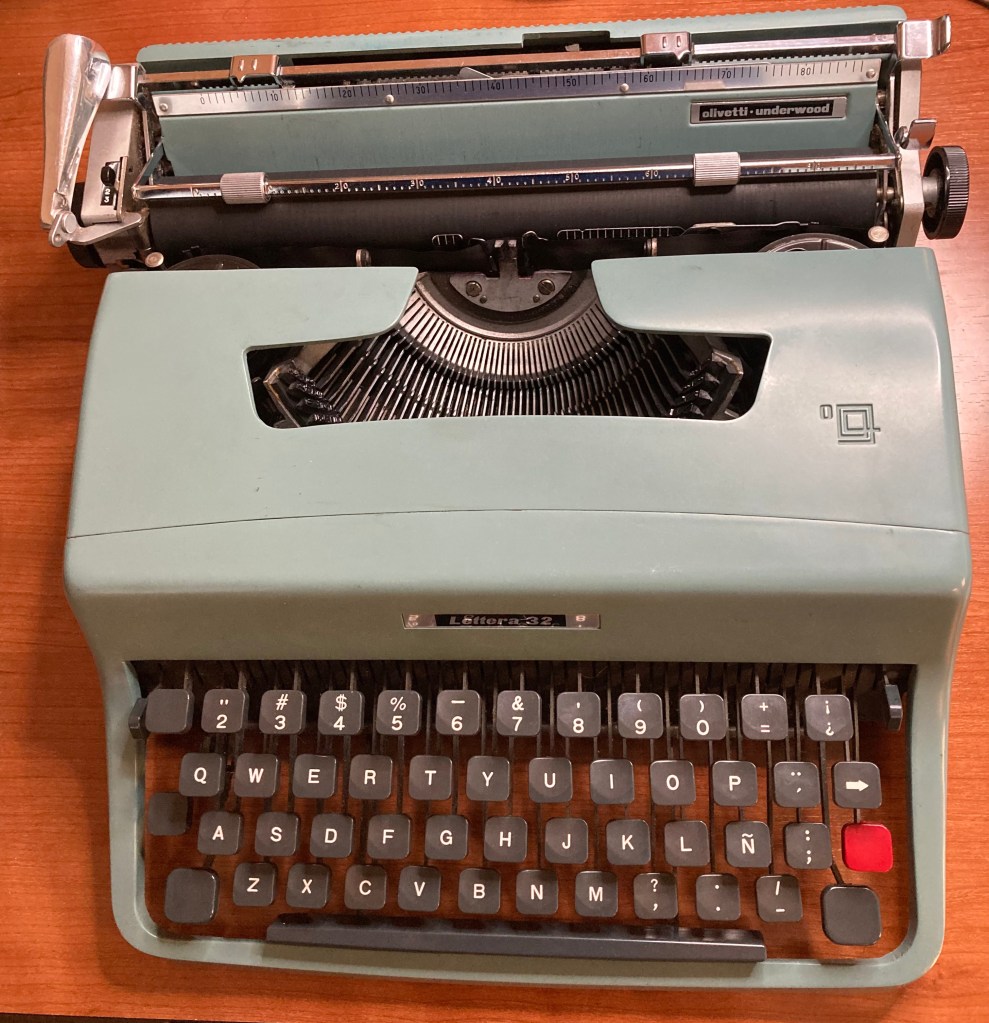

BUT: in the otherwise-fastidious recreation of that hotel room in Nouvelle Vague, the probably-Remington has unmistakably become…an Olivetti-Underwood Lettera 32. An anachronism, since Olivetti first made this machine in 1963—and the distinctive faceplate identifies it furthermore as a later iteration, probably from the late 60s. Catastrophe!

This machine is coded completely differently! Italian vs. American, stylish and sexy vs. boring and reliable. She might have even bought it in Paris.

Who even is Patricia, if this is her typewriter? Other than a time traveler?

Pour quoi?

In a lovingly-detailed recreation and invocation of a very specific time and place…why would Linklater get the typewriter wrong?

Well, maybe he missed it. As a cineaste friend of mine noted, “if I found out you knew more about mid-century typewriter manufacturing than Linklater’s production design team, I wouldn’t be shocked, exactly.”

But isn’t it more interesting if he didn’t? If it is on purpose? Consider.

Nouvelle Vague presents Godard as someone with a complicated relationship to writing. At best. A running theme of the story is that Breathless has no script. In pursuit of a purity of experience, a spontaneity, never before seen, he shot without one. The film used a camera that was too loud to allow synchronized sound, but did permit unique still-camera film that, spliced into long rolls, could capture natural light in extraordinary ways. That meant all the audio was dubbed later, and Godard could and did feed lines to the cast while filming…lines that he would read from scribbles in a series of Moleskin notebooks where he claimed to have the whole film plotted.

Which does not mean the Godard of Nouvelle Vague fears text: he begins each day at a cafe with a pile of paper upon which he makes notes in what Seberg calls “beautiful handwriting,” and sometimes communicates important info by passing those notes to those they concern.

What this Godard fears is committing to a text: to typing it up and saying, this is what it will be. The script manager helplessly flips a single page back and forth on her clipboard. The producer fumes at how this same spontaneous relationship to text extends to the relationship with time and budget: Godard won’t shoot if he is uninspired. Nothing on any of his private pages dictates how and when to make the film: they are just gaps of indeterminacy, as Wolfgang Iser says, that will lead to new possibilities yet unimagined.

The fungibility of printed text in the film also boggles the digital-era, backup-savvy viewer. Presumably, the treatments we do see bandied about are bare stacks of paper, without bindings or apparent copies. (Le mimeo is glimpsed once in the background of the office: it sits silent.) A single copy of the story itself is handed back and forth between Truffaut and Godard on a metro bench; the first assistant director carries a fistful of paper through a bar, responding to Godard’s insistence that he “show it to no one” by shoving the pages briefly into the face of an innocent customer with a smirk.

Where is the text? It is scribbled here, it is handed around there…it is none of these places.

There is no text for Breathless: the film is the text, and the film only seeks to capture the untrained and unplanned interactions that result from Godard’s willingness to commit fully to their pursuit.

At one point, Godard is frustrated with his two leads planning what they are about to do when camera rolls (Allez!)

“What are you filming?” asks a passer-by. (He is shooting on the street, with real people unknowingly serving as extras.)

In frustration, he snaps back, “A documentary about Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg acting out a fiction.”

Everything he didn’t want: people planning to do things, which means they will not actually be doing things. (“Though a documentary would have sync sound,” Seberg grumbles.)

That is what Godard wanted, and got. Live action!

And that is what he inspired in those who followed, including Linklater: to seek out reality as best they can contrive to. Linklater, who played with time itself in Boyhood and the Before trilogy–synchronically daring, insisting on time shaping what appeared and what went on the film.

Because the text isn’t in the script, and it isn’t in the typewriter.

And if it isn’t in the typewriter…maybe it isn’t in the choice of typewriters, either.

Typewriters make dead fictions to be acted out, this out-of-time machine seems to say.

This is alive.

Even in this recreation, homage, impression, of what might have happened seventy-six years ago in the process of committing life to film…the choice seems to say: this is alive, too.

Allez!

*I wish I could figure out how to share screenshots from Kanopy and Netflix, but that stuff is locked down. Check out the films themselves! Get Kanopy from your library!

**I had pretensions of using some Roland Barthes in here somewhere but it’s probably in everybody’s best interest that I didn’t.

***The Olivetti Studio 44, by the way, also graces Susie Myerson’s office desk in The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel–which is incongruous, being way more of a home machine. Until you consider that the office is being operated on a shoestring mainly to book Midge: she must have loaned it from home.

Lead image from NYT.